"Certainly, God speaks through everything and to everything, also to me. Everything that is reveals him; everything that happens is an effect of his guidance and somehow affects the conscience; he is palpable at the core of me. But all this remains vague. It is not enough to live by, not to live as I feel I must. It is ambiguous and needs the ultimate clarification that can come only through the word of God, and this he does not speak to everyone.

Specific revelation of reality and God's will comes to me only through people. Divine Providence selects an individual with whom he communicates directly...The idea that everyone is strong enough to bear immediate contact with God is false, and conceivable only by an age that has forgotten what it means to stand in the direct ray of divine power, that substitutes sentimental religious 'experience' for the overwhelming reality of God's presence. To claim that everyone could and should be exposed to that reality is sacrilegious. God is holy and speaks specifically only through his messengers. He who refuses to accept him through his chosen speaker, who insists on hearing his voice directly, shows that he either does not know or will not admit who God is, and who he is himself.

Romano Guardini, The Lord (1954), 250-251

Musings about the spiritual life and the mission of the Church by an Episcopal parish priest.

Thursday, August 31, 2017

Sharing the Word of Life: New Technology in the Church

From the Sounds of St. Francis, September, 2017

Then

another book was opened, which is the book of life.” Revelation 20:12

The Book of Revelation is perhaps the Bible’s most dramatic

and mysterious section. Revelation 20

recounts the climax of the story, the great Day of Judgement, when our Lord

will return to speak the truth upon all humanity and make all things new. It’s easy to miss the fact that the author is

also noting a significant change in communications technology. The Lamb, that is Christ, has a book, a book of life—a book, and not a

scroll.

Books—codices is the

technical name-were new-wave technology in the first century. The first mention of a codex in literature is

by the Roman poet Martial, who was born a few years after the death of

Christ. Before codices there had been

tablets of wax and clay, as well as scrolls.

The codex was a handy technology.

Its covers protected the contents and it was easy to find one’s

place. The paper could be written on

both sides, so it was more economical as well.

It took the codex a few centuries to surpass the scroll. Religious officials were inevitably among the

holdouts, with their preferences for the venerable, the beautiful, and the

familiar. In synagogues today, they

still read the Torah from scrolls.

But Christians were different.

Monday, August 28, 2017

The Man of Pride

“Now there arose a new

king over Egypt, who did not know Joseph.”

Exodus 1:8

There are seventeen people

named in the first section of the book of Exodus, from which today’s Old

Testament lesson is taken. The author of the book, which we will be reading

from on Sundays for most of the next three months, does a fine job of setting

up his story. He begins with Jacob, the

last of the great patriarchs, who resettled his family in Egypt. He gives the names of all twelve of his sons,

from whom Israel’s tribes are descended.

He recounts the birth of Moses, the eventual hero of the story. His older sister, Miriam is named, and we’re

even introduced to Shiprah and Puah, the midwives who delivered him. Seventeen people are named, but the narrator

can’t quite recall just who was king in Egypt.

This is certainly intentional, and highly

ironical.[1] Because the king of Egypt—probably the Pharaoh

Rameses II—was undoubtedly the most important man in the world at the

time. He held absolute power in the

world’s most aggressive state. He was

owner of all property in the world’s wealthiest state. The art and literature of the world’s most

advanced culture celebrated his exploits.

If he was, in fact, Rameses II, he had a harem so large that he left

behind at his death a hundred sons and fifty daughters, whose descendants

formed a social class, the Ramesids, that dominated Egyptian society for

decades after his death.[2] He was worshipped as a god in life, and a

massive monument honored him in death.

His was not a name anyone of his time could forget. But to the narrator, he is simply “a new king

over Egypt, who did not know Joseph.”

Friday, August 25, 2017

Iconclasm, White Supremacy, and the New Kingdom: On the Lee Statue at Duke

“You shall hew down

the graven images of their gods, and destroy their name out of that

place.” Deuteronomy 12:3

I spent a few days in

Durham, North Carolina last week, visiting college friends. The evening we arrived, the cable news

headlines were proclaiming that a statue of Robert E. Lee, set into the doorway

of Duke Chapel, had been literally defaced, chunks of stone hammered out by an

unknown vandal. A few days later, Duke’s

new president announced that the statue would be removed for the safety of

worshippers and “to express the deep and abiding values of our university.”

I have, like most of you,

taken notice of the removal of Confederate monuments across the South over the

past few weeks, and the hate-filled outrage that the action produced in

Charlottesville. But for me, this particular

action struck a bit closer to home. Our

host for the visit was one of my oldest college friends, like me, a student of

American history. He still sings in the

Chapel Choir where we met over twenty years ago, and serves on Duke Chapel’s

advisory committee. We talked about the

attack, the university’s response, and all the complicated issues evoked by it

late into several nights.

It may seem foolish, but

my first response on hearing about the vandalism was shock. I walked by the statue hundreds of times on

my way to services and rehearsals. It

had never struck me as an offensive image.

It’s an odd choice, to be sure, but so are the rest of the figures in

the doorway, who collectively form a Southern Protestant hall of heroes. My grumbles, such as they were, were reserved

for Thomas Jefferson, who stood next to Lee, a slaveholder and an avowed heretic. I

thought of the Lee statue as quaint, a relic of another era. We wouldn’t put it up these days, but eighty

years of presence afforded the statue a certain deference.

Wednesday, August 16, 2017

Zeal and Patience, Part IV

Originally published on Covenant, 19 July, 2017

A similar uncertainty surrounds the affirmations

about our essential unity of belief regarding the Holy Eucharist. It is true

that This Holy Mystery: A United Methodist Understanding of Holy

Communion affirms “the real, personal, and living

presence of Jesus” in the sacramental elements (though “in temporal and

relational terms”). However, assorted practices surrounding the celebration and

administration of Holy Communion in United Methodist Churches stand at some

tension with this claim, as they deviate so seriously from historical norms.

Much of the online discussion has centered on whether the

Methodist requirement that Holy Communion be celebrated with “the pure,

unfermented juice of the grape” can be squared with the Chicago-Lambeth

Quadrilateral’s that the Holy Communion be “ministered with unfailing use of

Christ’s words of institution and of the elements ordained by Him.” More

serious is the nearly universal United Methodist practice of admitting the

unbaptized to Communion and the widespread authorization for celebrating Holy

Communion by licensed local (unordained) pastors.

Sunday, August 6, 2017

The Eighth Day of their Lives

“And behold, two men talked with him, Moses and Elijah, who appeared in glory

and spoke of his departure, which he was to accomplish at Jerusalem.” St. Luke 9:30-31

Over

the last few months, I’ve had several conversations with people who are staring

down retirement. Some friends are

leaving their work with a deep sense of satisfaction, ready to take on some

long-postponed projects. Others are

worried about how they will fill the time and are looking for a way to hang in

for a few more years. One friend was

doing the most fruitful and fulfilling work of his career, but the funding ran

out, and he’s facing part-time work, something quite different. It might be marvelous, but I don’t think he’s

completely sold on it yet.

In

the back of most of those conversations lay a series of questions I suspect

we’ve all asked ourselves, even if retirement lies half a lifetime away: “Does

my life add up? Does it have meaning, this work into which I have poured so

much of my time and energy? Do I have a

legacy?” It’s worth reminding ourselves

that our privilege allows us to ask these questions of our work. Most people in history and most people in the

world today simply must toil on until their bodies give way. But for all people, life is unpredictable,

full of unexpected shifts, confusing blessings and overwhelming sorrows. We long to understand where our lives are

headed, how their true meaning will be revealed. But so often, in the end, there is only

confusion. We see ourselves only through

clouds of smoke, beset by doubt and fear.

Thursday, August 3, 2017

Zeal and Patience, Part II

As the Episcopal and United Methodist churches consider a full-communion agreement, this article continues the story of the zealous John Wesley and the patient Samuel Seabury, the founders of the two churches. It outlines a missed opportunity for a united church in 1784, and what the failure then may still be able to teach us today. The article was first published on The Living Church's Covenant blog on 12 July

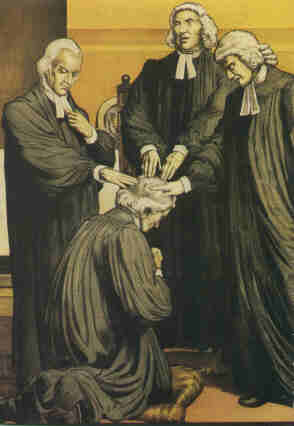

As Wesley sent off his letter, and Thomas Coke with it to come to America with the purpose of ordaining his preachers, another Anglican priest was also travelling about Britain. Samuel Seabury, bishop-elect of Connecticut, was pursuing a different potential solution to American Anglicanism’s pastoral crisis, one he believed to be essential to “follow[ing] the Scriptures and the Primitive Church.” Seabury was in search of three bishops who would consecrate him, so that episcopacy might be carried back to his native land.

Seabury’s zeal in pursuit of his cause cannot be doubted, but he was above all a patientman. For nearly a year and a half, he met with a number of English bishops to plead his case, some of them multiple times. Like Wesley, he was rather woodenly rebuffed by Robert Lowth, the Bishop of London, who could not imagine the prospect of consecrating a bishop who lacked a warrant from the Connecticut state legislature. Some of Seabury’s countrymen were using their personal contacts to work against his case, including the bishop-elect of Maryland, William Smith, who distrusted Seabury because he had been a loyalist. Deeply frustrated by delays and inconclusive answers, Seabury wrote to a fellow Connecticut clergyman, “I shall be at my wits’ end. … This is certainly the worst country in the world to do business in” (Letter to Abraham Jarvis).

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)