As the Episcopal and United Methodist churches consider a full-communion agreement, this article continues the story of the zealous John Wesley and the patient Samuel Seabury, the founders of the two churches. It outlines a missed opportunity for a united church in 1784, and what the failure then may still be able to teach us today. The article was first published on The Living Church's Covenant blog on 12 July

As Wesley sent off his letter, and Thomas Coke with it to come to America with the purpose of ordaining his preachers, another Anglican priest was also travelling about Britain. Samuel Seabury, bishop-elect of Connecticut, was pursuing a different potential solution to American Anglicanism’s pastoral crisis, one he believed to be essential to “follow[ing] the Scriptures and the Primitive Church.” Seabury was in search of three bishops who would consecrate him, so that episcopacy might be carried back to his native land.

Seabury’s zeal in pursuit of his cause cannot be doubted, but he was above all a patientman. For nearly a year and a half, he met with a number of English bishops to plead his case, some of them multiple times. Like Wesley, he was rather woodenly rebuffed by Robert Lowth, the Bishop of London, who could not imagine the prospect of consecrating a bishop who lacked a warrant from the Connecticut state legislature. Some of Seabury’s countrymen were using their personal contacts to work against his case, including the bishop-elect of Maryland, William Smith, who distrusted Seabury because he had been a loyalist. Deeply frustrated by delays and inconclusive answers, Seabury wrote to a fellow Connecticut clergyman, “I shall be at my wits’ end. … This is certainly the worst country in the world to do business in” (Letter to Abraham Jarvis).

Eventually, the bishops of the Scottish Episcopal Church agreed to interview him. Seabury’s letter to them is strikingly reminiscent of Wesley’s, invoking the providential significance of the moment and rejoicing in the opportunity to secure a church order that was, in Wesley’s words, “disentangled … from the English hierarchy”:

I apply to the good bishops of Scotland, and I hope I shall not apply in vain. If they consent to impart the episcopal succession to the Church in Connecticut they will, I think, do a great work and the blessings of thousands will attend them. … [P]erhaps for this cause … God’s Providence has supported them and continued their succession under various and great difficulties, that a free, valid and purely ecclesiastical episcopacy may from the pass into the western world.” (“Letter to Scottish Bishops,” Aug. 31, 1784)

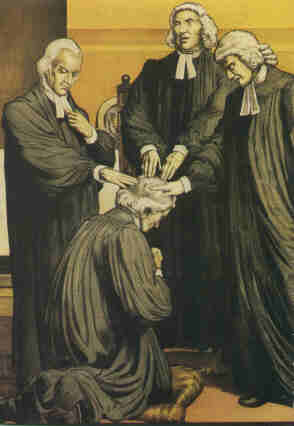

Seabury’s patience was rewarded when three Scottish bishops consecrated him at Aberdeen on Nov. 14, 1784. Ironically, on exactly the same day, in a Methodist meetinghouse in Delaware, Thomas Coke had his first meeting with Francis Asbury to discuss Wesley’s plan for establishing a Methodist church and ordaining its first ministers. That meeting would set in motion a process that would end in their joint ordination as the first Methodist superintendents (later bishops) at the famous “Christmas Conference” in Baltimore just six weeks later.

It could have been otherwise. Seabury had met with Charles Wesley during his time in London, and he had agreed to ordain Methodist preachers upon his return to America if he found them suitable candidates for the ministry. There’s no evidence that Seabury also met with John Wesley (or that, if he had, Wesley would have trusted that he would find success in his quest). But Charles Wesley found Seabury’s plan quite promising, and would scold his brother’s impatience in a letter to an American priest the following year:

Had they had patience a little longer, they would have seen a Real Primitive Bishop in America duly consecrated by three Scotch Bishops, who had their consecration from the English Bishops, and are acknowledged by them as the same as themselves. There is therefore not the least difference betwixt the members of Bishop Seabury’s Church, and the members of the Church of England.You know I had the happiness to converse with that truly apostolical man, who is esteemed by all that know him as much as by you and me. He told me he looked upon the Methodists of America as sound members of the Church, and was ready to ordain any of the Preachers whom he should find duly qualified. His ordinations would be indeed genuine, valid and Episcopal. (“Letter to Thomas Bradbury Chandler”)

Two Anglican priests in Maryland, John Andrew and William West, even met with Coke and Asbury during the Christmas Conference to suggest they pull back from forming a separate church. Acting on the assurances of their bishop-elect, William Smith, they promised the Methodists a high degree of autonomy, should their preachers consent to accept ordination by Smith. Their form of episcopacy would not be “either dangerous or burdensome,” and “could not be said to entangle men more than Mr. Wesley’s Episcopacy entangled them” (“Letter to William Smith”)[1].

Coke and Asbury replied that such an address “had not been forseen [sic] nor expected,” and recounted the hostility they encountered, often by Anglican clergymen on both sides of the Atlantic. Coke, who had inveighed against the moral laxity of Anglican clergymen in his sermon at the conference a day or two earlier, may well have been reluctant to associate with Smith, whose episcopal election would eventually fail to receive the required consents from General Convention because he was a notorious drunkard. Moreover, they could not act without approval from Wesley, and their course had already been set by the Conference’s actions.

Coke’s final word on the matter was a thoroughly unevangelical and fatalistic proverb of Aesop’s. Andrew’s letter notes how Coke replied

that for his own part he was inclined to think that our two Churches might not improperly be compared to a couple of earthen basons set afloat in a current of water, which so long as they should continue to float in two parallel lines, would float securely: but the moment they began to converge were in danger of destroying each other.[2]

Coke would eventually regret his words, and make overtures to Seabury several years later about a plan for uniting the two churches. Seabury kept his word to Charles Wesley, and would eventually lay hands on two of the Methodists that Coke had ordained at the Christmas Conference. But Coke’s latter letter went unanswered, and despite a few tentative schemes in the decades around the turn of the 19th century, the “couple of earthen basons” have remained apart, even as they are carried along toward a common destiny.

No comments:

Post a Comment